1856-- Mrs. Eunice Foote and Climate Change

Circumstances Affecting the Heat of the Sun’s Rays:

By Eunice Foote

From the American Journal of Science and Arts Nov 1856

Pages 382, 383

From a paper read before the American Association August 23rd 1856

My

investigations have had for their object to determine the different

circumstances that affect the thermal action of the rays of light that proceed

from the sun.

Several

results have been obtained.

First. The

action increases with the density of the air, and is diminished when more

rarified.

The

experiments were made with an air-pump and two cylindrical receivers of the

same size, about four inches in diameter and thirty in length. In each were

placed two thermometers, and the air was exhausted from one and condensed in

the other. After both had acquired the same temperature they were placed in the

sun, side by side, and while the action of the sun’s rays rose to 110 degrees in

the condensed tube, it attained only 88 degrees in the other. I had no means at

hand of measuring the degree of condensation or rarefication.

The

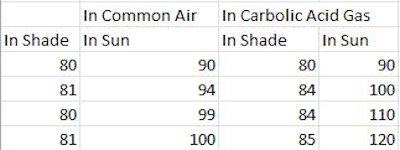

observations taken once in two or three minutes, were as follows:

This

circumstance must affect the power of the sun’s rays in different places, and

contribute to produce their feeble action on the summits of lofty mountains.

Secondly.

The action of the sun’s rays was found to be greater in moist than dry air.

In one of

the receivers the air was saturated with moisture—in the other it was dried by

use of chorid (sic) of calcium.

Both were

placed in the sun as before and the result was as follows:

The high

temperature of moist air has frequently been observed. Who has not experienced

the burning heat of the sun that precedes a summer’s shower? The isothermal

lines will, I think, be found to be much affected by the different degrees of

moisture in different places.

Thirdly.

The highest effect of the sun’s rays I have found to be in carbonic acid gas.

One of the receivers was filled with it, the other with common air, and the result was as follows:

The receiver containing the gas

became itself much heated—very sensibly more so than the other—and on being

removed it was many times as long in cooling.

An

atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as

some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger

proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action as

well as from the increased weight must have necessarily resulted.

On

comparing the sun’s heat in different gases, I found it to be in hydrogen gas

104 degrees; in common air, 106 degrees; in oxygen gas 108 degrees; and in

carbonic acid gas, 125 degrees.

You can't say we were not warned early about climate change!

Not surprisingly, an Englishman named John Tyndall "discovered" the same thing Foote did three years later. He was unaware of Foote's paper. For decades he was given credit for what has become the basis of climate science.

Comments

Post a Comment