1858-America's War With Paraguay

The US War With Paraguay--1858

Yes.

The United States almost went to

war with Paraguay in 1858.

Yeah. That Paraguay. The landlocked

country in the middle of South America, then about the size of Texas.

Congress authorized President

Buchanan “to restore American honor by any means including force if necessary,”

(similar to the Congressional authorization President Lyndon Johnson received

to launch the Vietnam War.) It was a serious operation which sent one

fourth of the US Navy (19 ships) and 2,500 troops to Buenos Aires to await

orders to sail 1,300 miles up the Paraná River for which they had few charts, past

well-armed forts, to invade a country for which they had no maps nor any idea

of the size of enemy forces.

And the President/dictator of

Paraguay, Carlos Antonio Lopez, originally thought he was signing a treaty of goodwill

and trade between the two countries.

If it had not been for cool heads of

an American navy admiral and the accompanying chief diplomat, a Missouri lawyer, America could have had its first quagmire more than a century

earlier than Vietnam.

In the end, US military operations

cost $3.5 million. Paraguay paid $9,600

indemnity.

Here’s how it happened…

In 1845 Edward A. Hopkins, 22, resigned

his commission in the US Navy after his third court martial. He was described

as arrogant, pushy, egomaniacal, aggressive, greedy and a liar.

For some reason Hopkins was

fascinated by South America, Paraguay in particular. He gathered as much

information on the country as he could and then approached President James K.

Polk in 1847 asking for a diplomatic posting to that country. Polk was

interested in establishing diplomatic and trade relations with the new

republics forming after liberation from Spain. He sent Hopkins to see then

Secretary of State James Buchanan along with a note recommending him for a

posting to Paraguay.

Secretary Buchanan had serious

doubts about Hopkins’ suitability—he knew Hopkins reputation and youth-- but the

president had recommended him, and Buchanan certainly could not find anybody

else to go.

It would not be until 1857 that the

US Congress would agree to fund a professional diplomatic corps. Until then consuls

and ambassadors were unpaid, expected to earn money by promoting their own

business interests in places they were stationed. The diplomatic appointments were

based on political patronage, family connections and bribes.

Hopkins had no diplomatic power per

se. He was simply to tour Paraguay

taking notes on their economy and inclinations to open relations and trade with

the United States. Hopkins was to regularly send reports to Washington.

Hopkins did as he was told—and then

some. In his tour, Hopkins befriended the president/dictator of Paraguay Lopez.

Obese, touchy, proud, and sly, President Lopez was eager for trade with the

United States.

Within three months Hopkins’

arrogance and self-confidence got the better of him. He far exceeded his

authority, claiming he had full US authority to mediate disputes between Paraguay

and Juan Manuel Rosas, dictator of Argentina.

When the president of Argentina

declined Hopkins’ offer, the young man wrote him such an insulting letter, that

Secretary Buchanan recalled him and published an official apology to Rosas.

Returning to the US, Hopkins spent

the next several years promoting a get rich quick scheme to wealthy

Americans. Hopkins proposed forming the United States and Paraguay

Navigation

Company which would have a lock on all business between the

two countries. Persuasive and smooth, Hopkins raised $100,000 for the venture,

including a large investment from the governor of Rhode Island. Hopkins was to

accompany the machinery, goods, and money to Paraguay and act as the manager of

operations there. Lopez treated Paraguay

as his private estate and Hopkins believed no enterprise could succeed there

unless protected by some diplomatic status. His investors persuaded the new

Secretary of State William Marcy, to give Hopkins hazy diplomatic status in

Paraguay.

Hopkins set out and got as far as

Montevideo, Uruguay where he learned the ship carrying the company goods and

machinery had sunk off the coast of Brazil. Still, Hopkins pressed on to

Asuncion where he was welcomed by President Lopez along with a $10,000 gift.

Hopkins set up businesses in tobacco and a sawmill. With President Lopez backing,

the businesses prosper. Translation, Lopez provided dirt cheap labor and took a

part of the profits.

As Hopkins set up businesses, Lopez

allowed the US Navy survey vessel Water Witch to map the constantly

shifting shoals and islands of the Paraná and Paraguay Rivers. As wide or wider than the Mississippi, and as

long, the rivers had to be mapped before commercial ships would dare sail as

far upriver as the Paraguayan capital, Asuncion.

Commander of the USS Water Witch was

one Lt. Thomas Jefferson Page. Lopez authorized Page to map the river only a

certain amount further north of Asuncion. A border dispute was brewing between

Paraguay and Brazil (which would lead to war in 1864) and Lopez did not want

Brazil to possibly obtain accurate maps of the area or to set a precedent of

allowing warships on that part of the river.

Lt. Page ignored President Lopez’

license to map no further north than a certain point. Page went a very long ways further.

Shortly before Lt Page and the Water

Witch returned to Asuncion in September 1854, Edward Hopkins spectacularly

insulted President Lopez and was ordered to leave the country. Hopkins’ brother

had been out riding with the wife of the French consul when they encountered Paraguayan

soldiers herding cattle. The corporal in

charge politely asked Hopkins and the lady to move to one side as he feared

their presence might cause a stampede. Hopkins refused, and sure enough, the

cattle stampeded, leaving the soldiers to round them up again. Angry and

frustrated, the corporal whacked Hopkins’ brother across the rump with the flat

of his sword.

On hearing of the incident, Edward

immediately rode to the presidential palace, shoved past guards and aides to

surprise President Lopez and his ministers in a meeting. Swearing loudly in English,

Edward Hopkins brandished a bull whip and threatened to use it on Lopez himself

if there were no apology forth coming. Surprised and astonished, not

understanding a word Hopkins had shouted, Lopez finally got a reasonable

account of the matter. He had the

corporal given 300 lashes. That wasn’t

good enough for Hopkins. He demanded an official apology in print in the

official newspaper.

President Lopez had had enough. There

would be no printed apology. Moreover, he ordered Hopkins to turn over certain

papers (probably business records) and immediately leave Paraguay. That’s when the Water Witch returned,

and Lopez found Lt. Page had mapped far beyond where he should have stopped. Enraged,

Lopez ordered the Water Witch to leave at once. Lt. Page felt he should help a fellow American,

so when the Paraguayans proved obstinate—not providing the paperwork in English

for Hopkins to leave among other things--he pointed the Water Witch’s

three guns at the Presidential palace and took Hopkins on board along with

papers Hopkins was supposed to turn over. The Water Witch then left for

Buenos Aires September 17, 1854.

Outraged, Lopez issued an official

decree forbidding any foreign warships from sailing Paraguayan waters.

In the meantime, the US Senate was

about to vote to accept the trade and relations treaty with Paraguay. The American consul in Buenos Aires--the only

American diplomate in southern South America-- had not proof read the agreement

before sending it on to Washington.

Some pedantic grammar queen noticed

the treaty referred to the United States as “The Union of North America.” It was obvious what was meant, but the treaty

was sent back to have the wording corrected and approved by President Lopez.

Months later, when the treaty finally

made its return to Lopez for his correction and signature, he refused to accept

it since the treaty was not in Spanish.

Back in the US, Hopkins loudly

proclaimed to the public and his investors, that President Lopez had violently

and greedily expropriated American property and then banned warships to prevent

retaliation and then refused to sign a trade and goodwill treaty. Hopkins’ backers were men with influence so

political wheels began to grind with a lawsuit to force compensation,

compensation far in excess of the $100,000 they had invested.

Things got worse.

Lt. Page anchored and re supplied the

Water Witch at the Argentinian river port Corrientes in

January, 1855. Corrientes lay a few miles from the Paraguayan border. Lopez

sent his son to see Lt. Page on the Water Witch. President Lopez still

wanted a trade treaty and recognition of his government from the United States.

Lt. Page and the president’s son’s

meeting was cordial. Lt. Page presumed relations

were patched up and all forgiven. The

next day, January 20, 1855, Page left along with 19 of his men on a planned

expedition to explore the Salada River. That same morning, Page put Lt. William

N. Jeffers in command of the Water Witch, ordering Jeffers to

steam north into Paraguay and re map the northern Paraná River.

By any standards, the Paraguayan Fort

Itapuri commanding the river at the border was formidable. Well-fortified heavy guns and several

thousand troops stood guard. Itapuri’s commander had received no word

the policy forbidding warships on the Paraguayan stretch of the Paraná had been

changed. (And it hadn’t been!) When the Water

Witch appeared there was some confusion. The ship was known to be a non-combatant

survey vessel but still…

Jeffers steamed on.

The next volley was in earnest,

ripping away much of the Water Witch’s rigging and shattering the pilot

house. Helmsman Samuel Chaney lay dying in the wreckage.

The ship’s puny weapons returned fire

as the vessel passed, finally steaming beyond the range of the fort’s guns.

Then Jeffers realized he was not safe for long.

He’d brought the ship into shallow water. There was only a foot between

his keel and the river bottom. The Water Witch could easily run aground

and be overrun by the Paraguayan army. The

only way out was to steam backwards along the way they came, past the fort once

more.

The fort’s gunners were skilled. Ten of their twelve shots damaged the hull of

the Water Witch as well as disabling one of its side paddle wheels. The

Paraguayan cruiser Tacuara appeared while Jeffers was desperately

repairing his ship. Jeffers seriously

considered engaging the Tacuara. He decided against it quickly. A lightly armed survey ship, partly disabled

and sinking, was no match for a fully armed cruiser. Lt. Jeffers barely managed to get the Water

Witch back over the border and escape capture.

When Lt. Page heard what had

happened, he angrily demanded (four times in two months,) the Navy provide a

heavily armed squadron to come destroy the fort “to teach a lesson and restore

the flag’s honor.”

Wisely, the US Admiral commanding

the meager American forces in the area refused him.

That was the end of it for several

years.

Newly elected, President James Buchanan

made his first address to Congress in December 1857. For some reason—perhaps,

because Hopkins’ backers were pressuring him, or perhaps because he thought a

foreign war would unite a country rapidly coming apart--Buchanan revived past

incidents with Paraguay nearly four years after the fact. Calling Fort Itapuri’s firing on the Water

Witch “a most unprovoked, unwarrantable, and dastardly attack,” Buchanan

went on: Paraguay had: seized and appropriated the property of American citizens

residing in Paraguay in a violent and arbitrary manner; upon frivolous and even

insulting pretexts, refused to ratify the treaty of commerce and free

navigation; and fired on the United States steamer Water Witch…and killed the

sailor at the helm, Samuel Chaney, while the ship was peacefully surveying the Paraná River.

Buchanan asked Congress to

authorize him “to restore American honor” even if he had to use force.

In

June 1858, Congress voted all the funds necessary to obtain satisfaction for American

honor, using force if necessary, including appointing civilian agents to

purchase suitable merchant steamships to be converted into war vessels for the

US Navy.

NY Herald Dec 9, 1858

The US Navy to Lease Ships

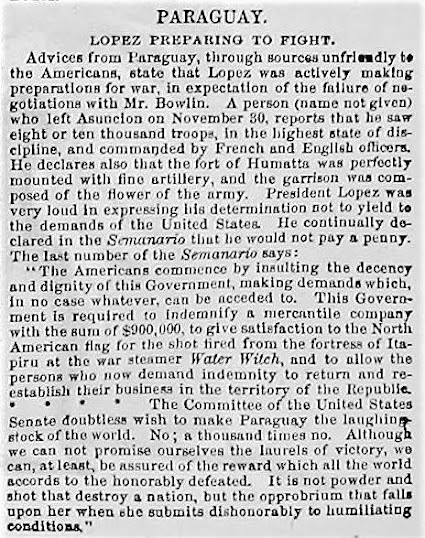

Below: NY Times publishes Lopez defiance February 1859

Buchanan

promised Congress a diplomatic approach would be attempted first. A lawyer, James Bowlin, former Post Master

General (and the man who had introduced postage stamps ten years earlier) was

chosen as representative and negotiator. Bowlin was to obtain ratification of the trade

treaty; negotiate no less than a half million dollars’ compensation for Hopkins

and his investors; obtain an apology for rudeness shown US Naval officers when

presenting the treaty; and at least $5,000 for the family of the dead helmsman,

Samuel Chaney.

Several months later, 19 ships carrying a total of 200 guns,

one fourth of the US Navy, “the Paraguay Squadron,” along with 2, 500 fighting

men steamed toward Montevideo, Uruguay. If no agreement with Paraguay were

reached, Shubrick was to sail 1,300 miles up the Parana river and bombard Asuncion

to rubble.

Shubrick’s force arrived in Montevideo, in December 1858.

The Paraguay Squadron--Harper's Magazine December 1858

Ambassador

James Bowlin reassured Uruguay and other nations the expedition was there on a

peaceful mission. In January, the US Navy started up the Paraná river. Ships with deeper drafts were left along the

way at several Argentine ports. Bowlin and Admiral Shubrick continued into

Paraguay with only one ship, the USS Fulton. Bowlin intended entering

Paraguay in a single ship to signal peaceful intentions. Lopez recognized that

and received Bowlin and the Admiral with great courtesy.

It

did not take long for Admiral Shubrick and James Bowlin to recognize true fault

lay with Hopkins, Lt. Page, and Lt. Jeffers. They recognized as well that the

incompetence of the American consul in Buenos Aires was a contributing factor.

Soon,

Lopez signed the trade treaty with the United States, opened Paraguayan waters

to American merchant ships, and promised a cash payment of $9,600 to Samuel Chaney’s

family.

But

Bowlin still had a problem. The final

issue was the matter of paying compensation to Hopkins’ investors. Buchanan had strictly instructed him to

accept no less than $500,000 from Paraguay to be paid to Hopkins’ investors. Neither Bowlin nor Shubrick believed the

investors were owed a dime given Hopkins’ outrageous behavior and the insane

demand for $900,000 in damages for an investment of only $100,000.

Bowlin

urged Lopez to agree to an arbitration commission, sure Lopez would win when

the facts came to light. Moreover, Admiral Shubrick recommended a friend, a good

lawyer licensed to argue cases before the US Supreme Court.

Sam

Howe, brother of Julia Ward Howe, was present as translator between Lopez and

Bowlin. Howe was nominated to be secretary

to the arbitration committee. Howe was a

bon vivant and later became known as a leading congressional

lobbyist. Lopez bribed Howe with a lump

sum to get the trade treaty passed correctly by the US Senate. Further, Lopez promised

Howe a commission of 2% of the amount below $500,000 the arbitration committee

decided.

The

arbitration committee was formed in mid-1859 but its final ruling was not

announced until August 1860. When it

came, it was no surprise. Hopkins’

investors were awarded nothing.

Assessing

costs and lessons from the expedition, the US Navy found the merchant vessels

leased were barely seaworthy to begin with and once converted not much

improved. A Congressional investigation

concluded it had been a corrupt way to award patronage to political allies.

Had it come to war, Adm. Shubrick had only seven hours’

worth of ammunition for his guns, and 2,500 men were far too few to defeat the

Paraguayan Army. Adm. Shubrick could

have blockaded the river, but Paraguay was poor enough it was self-sufficient.

A blockade would have little effect and to maintain such a blockade would have

forced American forces to rely on a supply line stretching over several

thousand miles back to the Eastern United States. Plus maintaining 2,500 troops

in South America would not be popular or worthwhile. (Keep in mind,

the total size of the US Army was 16,500 men and officers; 5,000 men were

engaged in the Mormon War in Utah, 2,000 more were keeping order in “Bleeding

Kansas, and the rest scattered over the newly conquered West fighting Indians

whenever White settlers broke treaties.

It’s little wonder that when South Carolina seceded in 1860, one of

Charleston’s forts was manned solely by an elderly sergeant, his wife and

kids.)

Not

only did the advent of the American Civil War make most of the treaty moot, but

Paraguay stumbled into disaster in 1864.

In 1862 President Lopez died. His son, Francisco, became president and border disputes with Brazil, Argentina, along with Francisco Lopez’ meddling in the Uruguayan Civil War, plunged the country headlong into what came to be called the Triple Alliance War. The Paraguayans fought fanatically, and it took six years to defeat Lopez’ army. In the end, Paraguay lost much of its territory and demographers have argued between 69% and 18% of Paraguay’s population died. One census after the war found a ratio of four women for every man and an even higher female to male ratio in some areas.

Harper's Magazine 1859

Afterwards---Lt. Thomas Jefferson Page left the US Navy when his home state, Virginia, seceded . For a while he was a colonel of artillery. In 1863, he was put into the Confederate Navy and sent to Europe to oversee construction of and command of the ironclad ram CSS Stonewall. His ironclad arrived in American waters too late to take part in the war, so he sailed for Havana and turned over his ship to Spanish authorities.

From Havana he went to Argentina where he helped found a colony of ex Confederates; became an adviser to the Argentinian navy and finally was sent to Italy as secretary to the Argentinian ambassador. He lived in Rome until his death in 1899.

Lt. William N Jeffers stayed in the US Navy. He commanded several ships, one of which took part in the invasion of eastern NC. Afterwards, he was briefly commander of the ironclad Monitor. In 1863, he was made US Navy inspector of ordinance. He continued in the navy after the war, commanding a frigate in the Mediterranean. He spent the final eight years of his service a chief of the Ordinance Bureau until his death in 1888. Before Paraguay, Jeffers had done a survey of Honduras. He took part in three naval bombardments of Mexican forts in the Mexican War. This experience probably caused his reaction to the Fort of Itapuri opening gun ports and running out guns.

Edward A. Hopkins continued roaming about South America when he wasn't in the United States pursuing his claims in courts. His final appeal was thrown out in the 1880s.

Commodore (later Admiral) William B. Shubick--remained loyal to the Union despite being a son of a wealthy South Carolina planter. He had served in both the War of 1812 and the Mexican War. Soon after the beginning of the Civil War he was promoted Admiral and forced to retire on account of his age in 1861 (70 years old) . He died in Washington DC in 1874.

James B. Bowlin was almost 30 when he left his native Virginia and moved to St. Louis. Diving into politics, it did not take him long to win Missouri's sole congressional seat in which he served several terms before a three year stint as ambassador to Columbia. After his service in Paraguay, he returned to his law practice in Missouri. He died there in 1874.

Some more original sources may be found at

The Water Witch Incident by Clare McKenna

Lt. Page's account of encounters and explorations in South America

Reminds me of the William Walker affair in Nicaragua...

ReplyDelete