Filibuster--when it meant something different

Filibuster--when it meant something different

Filibustering did not always mean

yak-yak-yak in a legislative body to delay passage of a particular law.

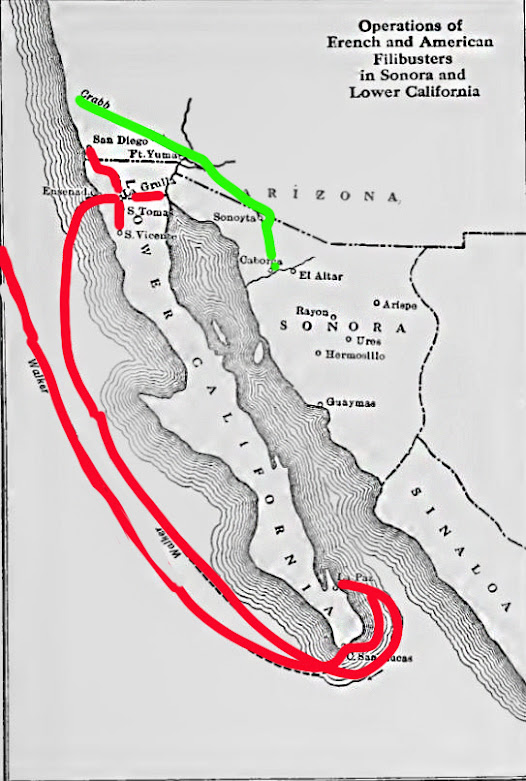

William Walker's Route into Mexico in red

In 1852, “filibustering” meant raising a

mercenary army paid with the promise of booty and armed by Southern slave

owners to take over Central American countries, reinstitute slavery, and then

apply for US statehood.

Napoleon’s invasion and subjugation

of Spain in 1809 removed Old World authority over Spain’s colonies in the

Americas, providing opportunity for rebellion and independence. Except for

Puerto Rico, Florida, and Cuba, Spain’s New World colonies freed themselves

under the leadership of Simon Bolivar. Most attempted to set themselves up

nominally as republics, offering men universal suffrage and abolishing slavery.

The new governments were weak, though, unstable, their boundaries and names often

shifting. Beyond Cuba and Florida,

Americans knew little about the new republics; in fact, did not even have

diplomatic relations with most of them.

With the addition of California and

the southwest to the United States in 1848, soon followed by the discovery of

gold in California in 1849, a canal across Central America to speed trade with

California and Oregon was needed. At the time, the quickest way across was to

steam up the San Juan River from Greytown on the Caribbean coast to Lake Nicaragua.

A very narrow strip of land could then be crossed to Rivas on the Pacific

Coast. Both British and French investors

were already negotiating with Nicaragua to build a canal across its territory. Filibusters

argued any canal joining the newly continent wide nation should be American

controlled.

With their tropical and semi

tropical climates, Southern planters saw an opportunity to expand the number of

slave states in the Union. Slave owning Americans could settle and take over

the governments of the newly independent countries. Texas had set a fine

example.

Filibustering was born.

Early filibusters were new Anglo

Californians who believed the US had not annexed enough of Mexico in 1848. Baja

California and Sonora seemed logical additions to the United States.

The most

famous filibuster, and the one that came closest to success, was a charismatic,

slightly built Virginian with gray eyes and lank blond hair. William Walker was unknown to the public when

he showed up in San Francisco in 1850. The publisher of the newly established San

Francisco Herald needed an editor. With polished manners and degrees in

medicine and law, and having recently relinquished his post as editor and part

owner of the New Orleans Crescent, William Walker seemed to be just the

man for the job. Walker had come West because, he said, he believed himself “to

be a man of destiny.” It did not take long before Walker decided editing a

newspaper was not the destiny he was destined for.

He

advertised for bold men to join him in an expedition to expand America’s boundaries

by adding Baja California and Sonora.

By

definition, men who had come to California to find a fortune were bold. Not

everybody could find gold so there was no shortage of volunteers.

In January 1853, contemptuous of

any Mexican resistance, Walker and his band of about 50 followers easily “captured”

thinly populated Baja California. Immediately, with grandiose ambitions, Walker

declared himself President of the Republic of Sonora-- though he never reached

there.

Walker set up a government appointing

various members of his army to the posts of “Secretary of the Navy,” “Secretary

of State,” etc. and

Before he

could send an envoy to the United States from his newly declared republic, the

Mexican Army showed up with over 1,200 men and artillery. Walker knew it was

time to run. He devised a “clever” escape by leading his men along a route too

rugged and dangerous for a large force to follow. It went through Apache

territory and across a desert. Not all his men made it back, but it did work. The

bedraggled group reached San Diego and were arrested by a US Army Captain in

San Diego.

The Federal

government wanted to jail Walker and his crew, but widely publicized by

newspapers—including his own San Francisco Herald, the public lionized

him for his exploits.

Walker’s

brash ambition and courage did not go unnoticed. George Bickley, later founder of a Southern

group of slave owners called Knights of the Golden Circle, approached

Walker with another scheme. The Knights

of the Golden Circle’s plan was to take over Mexico, Central America and most

of the Caribbean and turn them into slave states. Geographically, this would form a “Golden

Circle” with Southern slave states along the northern rim.

They wanted to back him to attempt

to take over the Republic of Nicaragua.

The United States wanted no part of

the scheme—it might provoke a war with France or Great Britain who were sending

ships to safeguard their interests in Central America. It also embarrassed the

US to be the “land of the free” seen taking over weaker states soon after

having pillaged half of Mexico. So many other filibuster schemes were hatched, primarily

to “liberate” Cuba, the US Navy had to stretch its resources farther to not

only supply enough ships to patrol for slavers off the coast of Africa but now

to also set up patrols to catch filibusters off the coast of Central America.

Walker was

not only successful, but he also managed to name himself president of Nicaragua

and hold onto the office for several months (the average term of all of the

country’s presidents.) He immediately re instituted laws permitting slavery.

Finally, Walker over reached. He seized steam boats owned by one of the

world’s richest men, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. Vanderbilt’s fleet was

very profitable taking supplies and miners up the San Juan River to Lake Nicaragua.

Forced to flee Walker was captured and sent back to the United States where he

was widely acclaimed once more. It was not

long before he was back in Central America a second time.

The second

time was not as easy as the first time.

Now, the

small, neighboring republics saw Walker as harbinger of a dangerous trend

threatening their own existence. In the end, the combined armies of Costa Rica,

Honduras, and Nicaragua, overwhelmed Walker’s mercenary band. Fleeing the country again, Walker was

captured by the British Royal Navy. The

British handed Walker over to the restored Nicaraguan government. There, Walker was tried and executed by

firing squad September 12,1860. He was 36

years old.

The Knights

of the Golden Circle disbanded in 1863 when it was obvious their dream of a

slave empire was not to be. The age of filibusters came to an end with the

American Civil War.

The next two blog entries are lengthy accounts published by a Washington, DC newspaper in 1909

after interviewing veterans of Walker’s mercenary armies, as well as some

shorter clippings from contemporary newspaper accounts.

Comments

Post a Comment