Kidnapped! Part 1

Kidnapped!

In March, 1834, seven year old Henry Scott sat quietly at his desk practicing writing letters. Most seven year boys find this boring, and Henry probably did, too. His life was about to become far more exciting. The door to the classroom slammed open and a New York sheriff and a well dressed Southerner, Richard Haxell, burst into the room. Haxell nodded at Henry, “That’s the one, Sheriff.” The sheriff yanked Henry out of his seat, announced Henry was a runaway (at seven?!) and left, Henry tightly in tow and squalling.

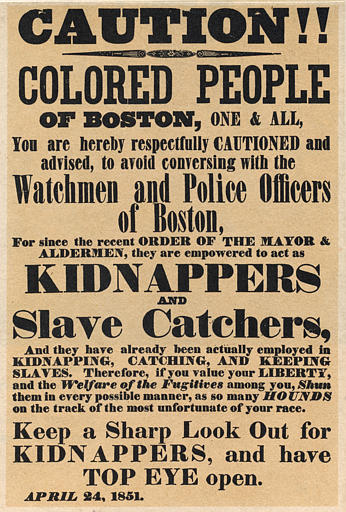

Free Blacks had been snatched off the streets of New York

more frequently as cotton plantations sprouted in the South, creating more demand

for slaves. Naturally, this produced more “runaways.” Free Blacks were not

exempt. Kidnapping Free Blacks right off

the street became profitable. The

kidnappers whisked their prey South to Baltimore to be sold. If stopped, they

claimed to be returning a slave. A victim would be snatched off the street and

hustled to the docks, smuggled onto a packet boat and sent South.

Ryker’s duty was to determine if arrested Negros were indeed free or runaways. Ryker and the police were each paid for every “slave” sent South. Not surprisingly, few people were ever deemed “free persons.” Along with the police and slave dealers in the South, Ryker had a lucrative business going.

But the community had never seen such a small child snatched

right out of his school desk.

The sheriff and Haxell took Henry before the City

Recorder. Haxell

insisted Henry was his brother’s property.

The black community turned out in force and testified one after the

other they had known Henry since birth. Ryker seldom faced any sort of

opposition. He declared Henry should go to the Tombs, New York City’s ancient

jailhouse, until Haxell could produce documents that Henry was a slave. Of course, Haxell couldn't. Scrapping

pennies together, the Black community raised enough money to have Henry

released.

Older children, ages eleven and twelve were preferred.

Few whites cared. Only when white children were taken by

mistake was there any outrage or notice taken.

And it did happen. If a Black child were not available, a white one

would do. Stealing a white child required they be “tanned,” their skin stained

dark enough to be sold.

When the US Constitution was written, most states, Northern

ones included, permitted slavery, the right of the slave owner to pursue and

take back his or her “property” was enshrined.

Since the writers expected slavery to fade, it was to be hurried on it

way as the Constitution prohibited importing slaves after 1808. Legal

enslavement was abolished by most northern states over the following 35 to 40

years. Racism was not.

People fleeing the overseer’s lash headed for the free spoil or free states.

Ironically and legally, they were less free than a Black in

1920 Alabama, but at least they were not slaves. As more slaves fled, the

demand for “slave hunters” increased.

Wealthy planters hired professionals who scoured the free states for

their runaways. Escapees could be legally seized and taken back to their

owners.

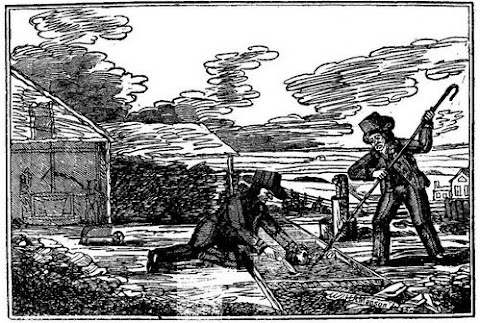

Rather dead than re enslaved. A dramatic illustration from Frank Leslie's Weekly Magazine

Kidnapping free Blacks right off the street became profitable. The kidnappers whisk their prey South to

Baltimore to be sold. If stopped, they claimed to be returning a slave.

Opposition to slave hunters grew.

As free Blacks integrated more into local small communities,

resistance to slave hunters grew. While their white neighbors would not dream

of allowing “free coloreds,” as they were called then, to vote or enter most

professions, they did not like seeing them kidnapped. Slave hunters could face outraged communities

and unsympathetic law enforcement.

New York City was different. The city was so bound up with Southern trade officials and bankers encouraged the slave catchers to keep their rich Southern customers happy. A large amount of the city’s wealth was related to slavery. Banks loaned money to planters as well as often selling their cotton and supplying luxuries. In turn, Wall Street made sure public officials supported the slave hunters. It was not long before the New York officials were getting a cut of the money as well. No real legal proceedings were required, beyond appearing before a Richard Ryker to have a cursory examination, their name entered in a register and then declared a runaway.

A Southern slave dealer would place an order. New York policemen would seize a likely match, hustle their victims before Ryker and send them South in a packet boat. Sometimes, the police would not even bother with Ryker. Returning to New York, the packet boat would bring money for the judges and policemen. This practice grew from the early 1830s on to about 1850 when New York passed a law requiring a jury trial for anybody seized.

The New York "Free Persons Law" requiring a jury trial put only a speed bump in the way of

the slave catchers. The free persons law was declared invalid because it contradicted the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law.

(more about that in another blog entry.)

From about 1850 or so on, Wall Street found a much more

profitable way to profit from the slave trade, but that, too, is for another blog

entry.

Comments

Post a Comment