Emancipation Proclamation

(Tenniel later became famous as the first illustrator of Alice in Wonderland)

Emancipation

Proclamation

Lincoln’s

Emancipation Proclamation was not a straightforward freeing of all slaves. In

fact, it pleased nobody except those held in bondage behind Confederate lines

on whom it had no effect. It was not meant as a humanitarian gesture, rather as an attempt to entice states in rebellion to rejoin the Union.

It was a

political ploy which did not work as intended.

Lincoln

waited to issue the proclamation until the Union had won a great military

victory—and Union victories were few and minor until September 17, 1862. US General

George McClennan stopped General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army’s advance

into Maryland and Pennsylvania at the Battle of Antietam. It was a battle larger than any previous encounters in the war. At Antietam more

Americans died in one day than had in all the US’s previous wars combined.

Antietam (called Battle of Sharpsburg by the South) signaled to both sides the war would be long and very bloody.

Made public

September 22, 1862, the proclamation declared that as of January 1, 1863,

people held in bondage in areas still in rebellion would be “henceforth

and forever more free.”

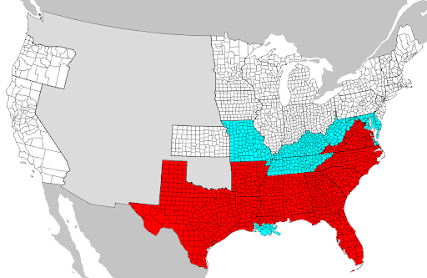

Exempted from being freed were

slaves owned by planters already behind Union lines; in three states, which had

not seceded, Missouri, Kentucky, and Delaware in which slavery was legal. The

northwestern counties of Virginia which would later form the new state of West

Virginia were also exempt.

The proclamation left slaves

already in Union controlled territory enslaved.

The proclamation was both carrot and stick to areas under Confederate control. It promised any state which before January 1, 1863, agreed to outlaw slavery in their constitutions, and free slaves on the condition their owners would be compensated would be readmitted to the Union.

Even Lincoln’s cabinet viewed the proclamation as useless, if not outright hypocritical. Secretary of State Seward, succinctly commented, "We show our sympathy with slavery by emancipating slaves where we cannot reach them and holding them in bondage where we can set them free."

The legalities could be complex. The Union had seized slaves originally as Southern property. As such, most of the men had been set to building fortifications for the Union Army. In a sense, they were now Union property. Once freed, the Army would lose a huge source of labor. White Union officers generally did not believe the 200,000 freed Black men who joined the Union Army would be as valuable as their labor building forts had been.

Southern newspapers as well as politicians and newspapers in the slave holding border states viewed the proclamation as a reckless act of terrorism, an act to incite slave uprisings. Newspapers called for the Confederate Congress to retaliate. It did so by declaring “any Negro soldiers captured would be hanged as slave insurrectionists.”

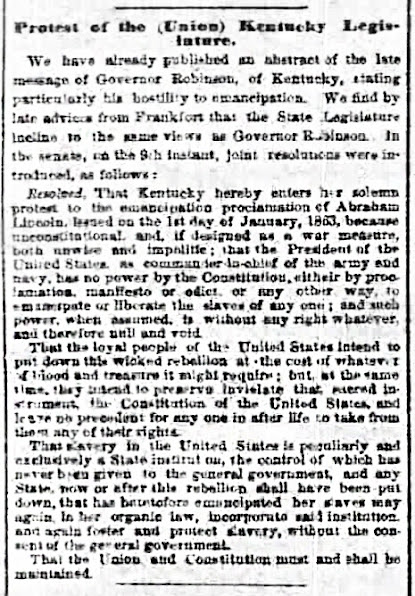

The governor of Delaware—a slave state that stayed with the Union—declared the proclamation “dangerous, ill-advised, and probably impractical.” Both Kentucky’s governor and legislature sent a formal protest to Washington, declaring the proclamation unconstitutional.

Ironically, the proclamation artificially drove up prices for slaves in the Confederacy. Should the Union pay a prewar price or a war time price?

If a Confederate state rejoined the Union under Lincoln’s offer, what would the Union do with escaped slaves from that state? Send them back to their owners? Were these people slaves or free Blacks? How much should the Federal government pay for the slaves to be freed?

Much of the North did not approve of slavery but were as racist or more so than the South’s population. There was fear that as soon as slaves were freed, they would flood Northern states, lowering the average White man’s working wage. Some Northerners resented possibly being taxed for buying slaves. In Union occupied New Orleans, the Georgia Sea Islands and Eastern North Carolina they were already getting a sample of difficulties integrating recently freed slaves into society.

No Confederate state took up Lincoln’s

offer to rejoin the union, so the practical effect was minimal at the time and

freed only a small fraction of the slaves immediately.

Comments

Post a Comment