The Truth About Texas

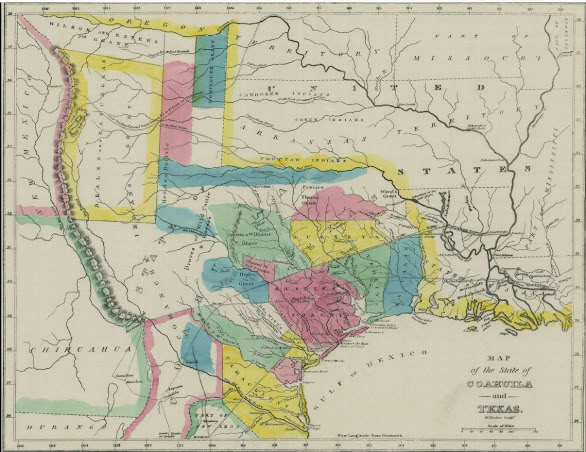

Map of the State of Coahuila & Texas

The Truth About Texas

"Y'all can go to Hell! I'm going to Texas!"

Davy Crockett on leaving his seat in the Tennessee legislature.

Spanish Mexico with vast stretches of thinly

or completely uninhabited lands needed hardworking immigrants as much as the

young USA. Spanish representatives touring the US to recruit settlers in 1820 met

Moses Austin, in southeast Virginia. Austin was agreeable and

enthusiastic about moving to Mexico so Spain granted him a large stretch of

land for him and his friends. Sadly, like Moses, this Moses never saw the

promised land. He died in June 1821 three

months before Mexico declared independence in September of 1821.

His son, Stephen F. Austin, took over his father’s dream of a new settlement in Texas and soon received recognition of the Spanish land grant from Mexico. In 1825 Stephen lead 300 families along with their slaves to the grant in Texas. The group numbered 1790 of whom 443 were enslaved.

Men were making new fortunes clearing land and planting cotton in the newly acquired states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. Texas' east coast along the Gulf was geologically an extension of the rich states further east. Cheap land cleared for cotton worked by slaves was the formula to get rich quick. With much of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana already claimed and settled, the only place left was east Texas.

There was one little problem with starting a plantation in east Texas. Mexican law outlawed slavery. Planters found an easy way around that. They simply ignored the law. Mexico City was far away and riven with continual infighting for power. Enforcement was unlikely to reach this far north.

The plantations expanded, more slaves were brought in and the men in east Texas prospered as much as those on plantations in the US.

Mexico City finally recognized all this newly prosperous land along the Gulf coast would be a rich source of taxes. Conflicts arose as much over slavery as over taxes when Mexican officials showed up. In 1830, Mexico forbade Americans from coming to Texas. Americans continued to arrive. By 1835 they vastly outnumber the natives by almost ten to one.

Additional trouble and confusion arose because the majority of the planters had never bothered to learn Spanish. (Does this sound like a vaguely familiar complaint about Mexicans in the US today?)

Forced to finally pay taxes and threaten with the loss of their slaves, the idea of seceding from Mexico gained popularity. And not just among the planters. The native Tejanos detested the far away and ever arbitrarily shifting politics and policies in far away Mexico City. What did they have in common with the far south Mexican jungle covered states anyway?

The two groups allied and soon the War for Texas Independence was underway. Santa Anna, being a dictator, took this badly. Owning slaves was civil disobedience, but not paying taxes, well, that was even worse. He gathered a sizable army and headed north to crush the rebellion.

After overwhelming Fess Parker and John Wayne—I mean Davy Crockett and Jim Bowie—at the Alamo, Santa Anna marched further north and met crushing defeat at the battle of San Jacinto. He lost a leg in battle and saved the leg and carried it as a political shrine for years afterwards. (Dan Sickels, a Union general would learn from this and do the same thing after Gettysburg.)

The Republic of Texas enshrined slavery in its constitution and made both English and Spanish the official languages.

The truth is Texas never wanted to be an independent republic. Left on its own, The Republic of Texas faced the same problem as Mexico --rich landowners did not want to pay taxes, meaning Texas would remain impoverished. The plan from the beginning was for Texas to apply to be annexed almost as soon as it was free from Mexico City's rule.

There was a problem from the American point of view. It would upset the carefully balanced and painfully negotiated Missouri Compromise of 1820. The Missouri Compromise didn't settle the question of slavery, but it did sweep the whole issue out of sight and let the US deal with other growing pains. Fearing Texas would be admitted as a slave state, further tightening the Southern states' grip on the power of the US Senate, Northern states adamantly opposed admission of Texas into the Union. Texas claimed northern borders far beyond the Missouri Compromise line. To join the Union, Texas had to cede much of its claimed northern territory.

Texas was stuck with being an independent republic. At least slavery was legal in the republic but in its nearly ten year existence, the Lone Star Republic was deeply in debt. Not only did the Northern states not want another slave state in the union, but the US as a whole was reluctant to take on responsibility for Texas' huge debt. A US Congressional report showed Texas' debt at the end of one year of independence was $1 million. By the time Texas was admitted to the union, its debts totaled a bit over $7 million.

When Texas was finally admitted to the Union, there was one small detail left unsettled with Mexico—where exactly, was the southern Texas border? Texas insisted it was the Rio Grande River, and Mexico declared no, no, no-- it was the Nueces River farther north.

Newly elected President James K. Polk had bigger problems than the Texas border. A war with Great Britain loomed over the border between what was then called “the Oregon” and Canada.

Common sense suddenly struck both sides when they realized neither could afford a war to be fought in such a distant place, plus the English didn’t want a repeat of the War of 1812 thirty years before.

The northern border settled, Polk and his Secretary of State James Buchanan, turned their attention to Polk’s real ambition, “Manifest Destiny,” the vision of the United States stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific was only partly accomplished by acquiring Oregon. A large chunk of Mexico would do nicely to complete things. Some in Polk’s cabinet advocated annexing all of Mexico.

How to start a war with Mexico that would find public support? There was the matter of the undecided border with Mexico.

Polk sent an American dragoon regiment (mounted infantry) to the Rio Grande. Santa Anna decided two could play that game and sent some troops north.

Now things get hazy. Polk went to Congress claiming American troops had been attacked on the north side of the Rio Grande. American blood spilled on American soil! An insult to American honor! In an era in which matters of honor were settled with duels, national honor had greater meaning and power.

Trouble was, where had this happened exactly—if it had happened at all? A bumpkin first time congressman from central Illinois, the Honorable Abraham Lincoln (WHIG--IL), introduced a resolution. Called “The Spot Resolution,” it demanded President Polk declare the exact spot where this bloodshed had taken place before Congress voted on war. Polk and the Democrats were furious. How dare Lincoln question the integrity of the President! Worse, another young congressman, The Honorable Charles Wilmont of Pennsylvania, introduced an amendment to the declaration of war that any land annexed from Mexico could not be turned into slave states even if most of it fell south of the line designated in the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Both Wilmont and Lincoln’s resolution and amendment were overwhelmingly voted down and both men lost their elections the following year.

Polk got his declaration of war against Mexico, a war he confidently expected to be over quickly—if a bunch of Texans could beat Mexico, Mexico could hardly stand against the might of the entire American Republic.

It didn’t work out that way. While the American army went from victory to victory, progress was slow and casualties high. There was friction between the professional American Army and the hordes of untrained and undisciplined regiments of US volunteers. The volunteers committed atrocities and the Mexicans responded in kind. Some of the fiercest Mexican fighters were former slaves who had escaped to Mexico and feared being returned to Texas if captured. The war dragged on several years and as casualties mounted and stories of atrocities on both sides filtered back, Polk feared the war would be a liability in the approaching 1848 election.

The Mexican-American War ended before the elections with Mexico losing a large chunk of sparsely inhabited land and over which it had never exerted effective control.

Junior officers in the American army who would be generals on both sides in the Civil War gained valuable experience. Jefferson Davis, an 1824 West Point graduate was hailed as an American hero. As colonel of the First Mississippi Volunteers, he was wounded leading a charge that turned the tide of one battle. Robert E. Lee, U.S. Grant and dozens of other officers would use their experience against each other fifteen years later.

Polk need not have worried about the 1848 election—he was too sick to run. Polk died in June of 1849. Under his four years of administration, the United States acquired more land than under any other president before or since.

And Grant was right.

PS-It's well known Texas was also given the right to split into four additional states. In modern times, this will never happen--Texans would never be able to agree which one was the "real" Texas.

Comments

Post a Comment