Journalism -The rise of national newspapers and magazines

Journalism

Of all the

puerile follies that have masqueraded before High Heaven in the guise of

Reform, the most childish has been the idea that the editor could vindicate his

independence only by sitting on the fence and throwing stones with impartial

vigor alike at friend and foe.

--Whitelaw

Reid, Republican Editor of the New York Tribune 1879

October

30, 1847

“We hope

to see the day when the press is regarded as an avenue to distinction as eligible

as the other learned professions. It

affords opportunity which other professions do not for the exercise of the

highest talent and largest attainments in a direction to sway the minds of

people, to enlighten their ignorance, and uphold and elevate public morals.”

The New

Orleans Picayune

Since this is a blog based on what newspapers told the public it is probably best to start with a brief examination of how newspapers were printed and distributed as well as the standards of reporting and advertising.

Newspapers were the first “bulk mail.” In 1792,

recognizing the importance of newspapers, Congress set a special mailing rate

of one and a half cents while the rate for letters was six cents. Most

newspapers consisted of four pages with eight columns of type on each page.

Subscriptions might be $2/year for weekly or twice a week newspapers which were

generally delivered by mail. There

was not always enough news, so columns were filled with sentimental poetry,

jokes, and romantic stories scattered indiscriminately among articles on

politics and prices of agricultural products. Often, editors engaged

“correspondents” to cover an event, what we call “stringers” today. Locals

would write long travelogues and the editors were likely to print them.

Iowa News Nov. 1860

Illustration was time

consuming and expensive to create, consequently, pictures were generally only

used in advertisements, and even they were small generic pictures such as a

hand and finger pointing, or the outline of a carriage. Few advertisers went to

the expense and trouble of having line engravings done to illustrate their

product.

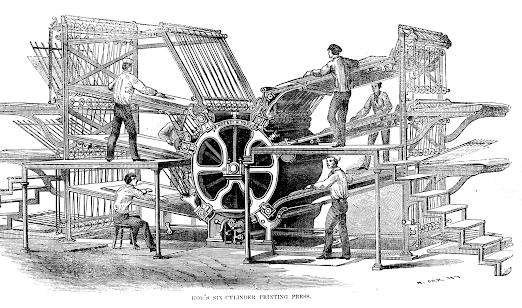

By the late 1840s a flood of newspapers started in the US. This newspaper flood was the product of three technology advances. A New York City mechanical engineer, Richard M. Hoe, patented a practical steam engine powered rotary press in 1847. Printing could be done much faster than earlier methods. Initially, the steam powered rotary press could print about 10,000 eight page newspapers an hour. Hoe soon added two important features to his printing press--the pages could be cut and folded, coming off the press ready to be mailed or delivered and a clock and counter showing the time and the number of newspapers printed so far.

New York

Herald October 29, 1847

“With Mr.

Hoe’s new invention, and the electric telegraph, we are beginning another and

greater revolution in the newspaper press, which will be felt in every avenue

of social life, in less than ten years.”

Horace

Greeley, editor

Like steamboats and trains, the presses

became more and more efficient, reaching about 35,000 pages an hour by the late

1860s.

To produce thousands of newspapers an hour much

cheaper paper was needed. Huge rolls of cheap paper made from wood pulp

answered that need. Previously, paper had been made from a

combination of cotton, cotton rags, and older paper. Rag paper as it is called,

is much superior in quality to wood pulp paper. It is also much more expensive,

and, at the time, it was not possible to make in large continuous rolls. Wood

pulp paper has a high acid content which causes it to turn yellow and brittle

quickly. Rag paper has low or no acid, so it does not turn yellow and become

brittle. (Books printed up until the 1840s generally remain in better physical

shape than ones printed in, say 1880 due to rag paper and leather covers.

Cheaper books on wood pulp paper bound with wood pulp cardboard do not last.)

Still,

editors needed a lot of readers to absorb the increased production and

distribution. In 1847 The New York Herald claimed 25,000 readers while the combined total of all the newspapers in Washington DC was about 2,000.

There

was a solution to that. A constantly

growing wave of immigration boosted America’s population from 17 million in

1840 to thirty million in 1860. Newspapers were published in German, French, Spanish,

Chinese, Czech, Swedish as well as English.

An

editor needed a modern way to distribute far more newspapers. The basics of

steam power that speeded up printing applied in transport as well. New post

office contracts with steamboats, trains, steam ships and steam driven coastal

packet boats moved mail much faster than old wagon overland routes.

This

left only one more problem: how to gather news to print, whether foreign or

close to home. Generally, newspapers were one to three-man operations. News not

strictly local was lifted from other newspapers. Editors sent each other copies

of their papers and, as long as there was attribution of the source, it was

considered permissible to publish stories from other papers. Newspapers, if

they had full time or even part time reporters, paid the staff poorly. Papers were very

local affairs and often the editor did the reporting, typesetting and selling

ads by himself.

Never

before had the public had so much access to the news of the world around them.

What were they to think of it?

Newspaper

editors knew exactly what to tell readers to think. Many newspapers were sponsored

or underwritten by special interests—railroads in particular-- and political

parties. Subscription fees and advertising supplemented income from backers.

Consequently, nobody expected a newspaper to be unbiased or even reasonably

truthful. A Democrat in a town might

read a Democratic sponsored paper while another man in the same town would read

a Whig newspaper. (Hello, Breitbart and MSNBC!)

In

contrast to modern newspapers, the front page served as the place to publish

poetry, humor, and fiction. As much as half the front page might well be ads.

The second and third pages delivered the news. Local agricultural news, city

council meetings, trials, train and steamboat schedules along with legal

notices of estate settlements, sheriff’s auctions and the

like. The fourth page tended to be advertising along with more

business news such as the cotton market at New Orleans, or the price for pigs,

tobacco, and corn in different locales. There were always ads for a variety of

quack medicines; ads for “ladies’ apparel” newly imported from France or “the

North.” Other ads touted everything from hardware to bookstores, private

schools, and local services.

News gathering itself was

erratic. Reporting standards were unknown and each editor decided for themselves

how factual or important news was before printing. In the 1850s over 2,000 newspapers

participated in some sort of swopping, but again, it was generally of

like-minded newspapers. Postage for

newspaper exchanges were very low, less expensive even than a regular newspaper

subscriber rate (and that was pretty low to start with compared to a letter)

Anticipating

the Transatlantic cable in 1857, six major New York newspapers came together to

form what would become the “Associated Press.” Editors across the country willing

to pay a monthly subscription price would receive daily twelve hundred word

telegrams from the Associated Press summarizing the day’s news from the major

papers. The transatlantic cable broke after a few weeks and was not restored

until 1867, but the Associated Press endured. It was a shock to men in power when

they suddenly realized eight underpaid newsmen in cramped second floor offices

in New York City wielded enormous influence over what the public should know

and how they should view events.

Being a newspaper editor

meant one could--and should--expect some sort of violence from offending

another newspaper editor or a prominent citizen. An editor who didn’t have at least one or two

threats hanging over him was hard to find.

When Mark Twain wrote his satirical essay, Journalism in Tennessee,

he had to stretch satire quite a ways before it exceeded reality.

One pair of newspaper

editors got into a duel using an umbrella.

March

16, 1849 from the NY Herald That

Fight—The Louisville (Ky) Journal, of the 10th inst,

says—F.P.Blair Jr., and L. Pickering, editor of the St Louis Union, who

had lately a personal warfare in the papers, met in the streets of St. Louis on

Monday. Blair attcked Pickering with an umbrella, when both drew weapons, but

no harm of consequence was done. Blair evidently got the best of the fight.

August 24, 1860, in

Decator, Missouri “Mr. Charles Shepherd was so much

excited by a fight between T.A. Green, a young lawyer, and Mr. Davis, editor of

the Gazette, that he expired in a few minutes. Green, it seems, undertook to pound the editor

for criticizing a piece of his original poetry.”

Just how deadly was being an editor?

The history below of the Vicksburg newspaper is taken from

the Library of Congress website

The

Vicksburg Press

The

first paper ever published in Vicksburg, Mississippi made its appearance on

Wednesday, the last day of March 1825.

It was called “The Republican,” published by Wm.H. Benton. …The latest dates in

that issue were fifteen days old from New Orleans; a striking contrast with the

present advantages of the Vicksburg dailies when the magnetic telegraph transmits

the news with lightening rapidity, and the mails, about which the tardiness of

which we so much complain come through now in fewer hours than it took days.

“The

Vicksburg Sentinel” was at one time one of the most influential papers in the

State. It has numbered among its editors some of the finest minds in the State;

but a most remarkable fatality has followed most of them. The paper was founded

in 1837, by Dr. James Hagan and Dr. Willis E. Green…It was started as a States

Rights paper of the Calhoun school… espousing the cause of the Nullifiers. It

soon became a regular Democratic paper and was famous for the violence with

which it supported the Democratic organization, and the bitterness with which

it assailed its adversaries. Dr. Green was not long connected with it and on

his retirement Dr. Hagan became the sole editor. Dr. Hagan was involved in

several street fights, but he fought but one duel, with an editor of “The

Vicksburg Whig,” Gen. Wm H. McCardle…at which the latter was wounded in the second

fire. He was killed in 1842 in a street rencontre by Daniel W. Adams of

Jackson, then a member of the same political party. The difficulty was

occasioned by an article in Dr. Hagan’s paper, reflecting on the father of Mr.

Adams. During the editorship of Dr. Hagan he was assisted by Isaac C. Patridge,

father of the present editor of the “The Vicksburg Whig,” who died of yellow

fever in Natchez in 1839. He was afterward assisted by Dr. J.S. Fall, who had

several fights, in one of which with T.E. Robbins, Esq., of his own party, was

wounded.

Dr. Hagan was succeeded as editor by D. J. Brennan, his executor. Mr. Brennan edited the paper but a short time, when he was succeeded by James Ryan, an Irishman of talent. He was killed in a duel by R.E. Hammet, then editor of “The Whig.” Ryan was succeeded by Walter Hickey of Natchez. He had several difficulties and was wounded repeatedly. In a rencontre with Dr. Maclin, of this city, the latter was killed. After retiring from the paper, Mr. Hickey was himself killed in Texas. A man by the name of John Lavins, who had been publisher during Hickey’s editorship, succeeded Hickey as editor. During his connection with “The Sentinel” he was imprisoned by Judge Coulter, of the circuit court, in consequence of the course of his paper. After leaving Vicksburg he went to Hernando in DeSoto county and established a paper there. “The Sentinel” then passed into the hands of Messrs. Jenkins and Jones, being edited by the former gentleman. He was killed in a street fight by Henry A. Crabbe, at the time a young lawyer of Vicksburg. Crabbe, a few years ago was murdered in Sonora, together with a party of other Americans. Mr. F.C. Jones succeeded Jenkins, but he did not remain long connected to the paper. Jones drowned himself not long since between Vicksburg and New Orleans.

NEWS FROM ST. DOMINGO—The telegraph has

announced that the Spanish consul at St. Domingo has induced the Dominican

government to recall a treaty made with the United States. A correspondent of

the New York Herald says that Segovia, the Spanish consul, is using every

effort to get the government under the domination of Spain. Mr. Galvan, an

editor, having exposed the plan, was waylaid, and shot one of those who

attempted to assassinate him. He fled and the writer says: It is supposed that

the fugitive from this packed tribunal of crime, may be aboard the American

schooner Elliott, now lying outside and bound for Boston. Segovia had forbidden

the vessel from going to sea until he has searched her with his Spanish marines

and Negro guards, to ascertain that Galvan is not on board. He has sent orders

to the Captain of the schooner that if he presumes to get up his anchor for the

purpose of going sea, he will be fired upon by the Spanish vessels of war that

command him with their guns. The United States Commercial Attache, Mr. Elliott,

has instructed the captain of the schooner to pay no attention whatever to the

threats of the Spanish Consul and not under any circumstances to permit the

search of his vessel by this self-constituted police officer and that when

ready and upon the usual clearances of the proper authority of the customs, to

go to sea.

As the Civil War started, editors realized people

would buy newspapers for news, not ads, legal notices and gossip. There was

voracious demand for firsthand accounts of battles and deeds of daring do. To attract more readers, the largest papers

hired both war correspondents and war artists. Only a few of the large newspapers,

usually large daily papers, would send out what we’d call war

correspondents. Moreover, they might

well be sent to cover only troops from a particular state or area, matching the

location of the newspaper. Smaller

newspapers depended on newspaper swops from large dailies to provide war

coverage. Reporting on local units was

usually in the form of letters from men serving at the front. Telegraph service

became unreliable as armies cut each other’s lines and was so expensive in any

event, nobody would dream of sending a long story. This would have an impact on writing styles.

Before the Civil War writing was full of florid words in long sentences, often

spiced with Latin or French. This was thought to imply authority and

credibility. Telegraph charges were based on the number and length of words

sent. Concise writing with short words was required now to cut costs.

Local

reporting and editorials retained their over blown, florid and idiosyncratic

style no modern editor would tolerate. “…the scoundrel then drew a

second pistol and blew poor Mr. Smith’s brains out.”

Before the Transatlantic Telegraph Cable was laid

you can see how long it took news for Europe or further abroad to arrive

by ship

The Confederacy formed a central news organization,

The Press Association, which never had the reach nor influence of the North’s

Associated Press. During the Civil War

newspapers were exchanged along with prisoners of war. Too, women on both sides

could obtain passes to cross enemy lines and would go with one set of

newspapers and return with another. Prisoners of war exchanges routinely

included an exchange of newspapers. It

was not at all uncommon for newspapers on both sides to reprint each other’s

news. A Georgia paper might begin a story, “New York newspapers of March 3rd

taken from Yankee captives report that…”

Two ads below demonstrate shortages of labor to even produce a newspaper in the Confederacy by early 1864

To Printers

TEN GOOD COMPOSITORS can find permanent employment at the highest wages and exemption from field duty (if not a member of a company of Confederate service) by applying to

EVANS&COGWELL

State Printers

Columbia, SC December 21, 1864

The Evening Star (Washington DC) reported March 17 1854

A notice in the Richmond Dispatch about the South Carolina newspaper ad above hints at how scandalous employing women in journalism was

Four young ladies are now engaged learning to set type in the office of the

And inflation forced up Confederate Subscription rates

War artists were rare. Matthew Brady sent teams of photographers out with the Northern troops but could take only static scenes of landscapes of battlefield or the dead in the aftermath of battle. Brady would peddle these photos to news magazines for their engravers and woodcut artists to copy. The war artists provided scenes of the action. Like modern combat photographers, they had to be willing to go in harm’s way. Most would climb a tree or seek a high spot from which to observe the battle to make very rough quick pencil sketches and notes. After the battle, the artists made finished drawings from some of their quick sketches. Among this cadre of men were Thomas Nast, the future’s first political cartoonist and Winslow Homer, later, one of the great American artists of the late 19th and early 20th century.

Above, one of Thomas Nast's war time sketches after being copied by an engraver at the publication

Below, Thomas Nast's original from which the engraver worked

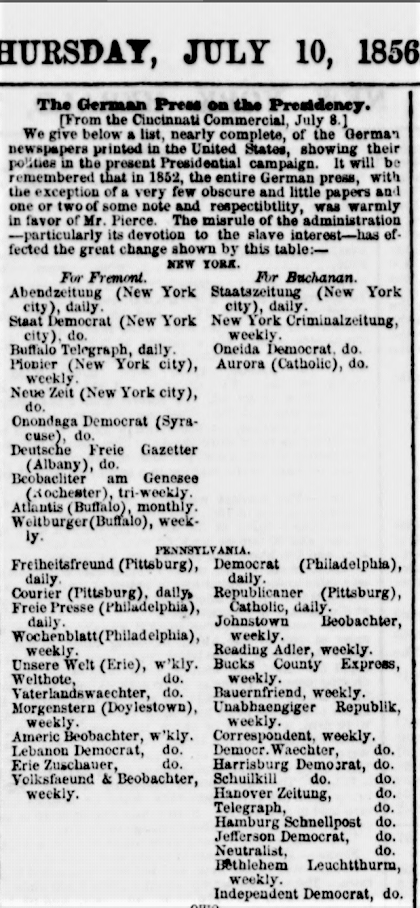

After English, the most

widely used language in American newspapers was German. Its influence can be

guessed by an announcement in the Richmond Dispatch of the formation of

the Richmonder Anzeiger in 1864. Even

a small town such as Goldsboro, NC had a German language newspaper for several

years after the Civil War. And as immigrants came from around the world,

newspapers were published in many languages.

As mentioned before,

newspapers were expected to have a sharp and discernable bias towards one party

or the other. In 1856 The New York Times

printed seven columns listing newspapers all over the country along with their

political stances, whether they supported James Buchanan, Jon Fremont or

Millard Phillmore for president. Note the number of newspapers published in

German—and even Welsh!

Judging

by the mastheads below of the newspapers charged between $2 and $3 a year. Here are some samples

Copyright issues were not

completely settled. The New York

Herald continuously slammed the New York Tribune for stealing the

novel by Thackery the Herald was serializing. General interest magazines developed from the

late 1840s on. The magazines too became

great publishers of serialized novels.

In

1849, the New York Herald pulled no punches in its criticism of the New York

Tribune

Nearly a decade later, in 1858, the Harper’s Weekly was having the same problem with the Tribune

Whitelaw

Reid’s praise of advocacy journalism quoted above faded by the early 1890s.

Powerful

publishers James Gordon Bennett and Joseph Pulitzer realized there was more

money to be made in advertising than party patronage. These two were the first

to realize increasing their circulation, they could charge more for

advertising. Railroads and the telegraph had made wealthy nationwide

businesses possible, and those businesses wanted to advertise to the widest

possible number of customers. To achieve wider readership, their

newspapers had to offend far fewer readers. Overt prejudice had to be dropped

or toned down.

Ironically,

this led to the basis of the modern journalism philosophy of “just the facts

without fear or favor.”

Comments

Post a Comment