IT'S 1848---AND THE INTERNET IS DOWN AGAIN!

Morse introduced his method of telegraph in 1844 with a 40 mile long line (66km) from Baltimore to Washington, DC.

By 1848 thousands of miles of telegraph line had been strung with systems of trained operators, repairmen and financers all in place. Like modern day Silicon Valley, independent companies proliferated. The telegraph was providing new jobs both in construction and in working the message offices.

Individual telegraph companies had different locations and served different areas of the country.

For example: the Washington DC paper, The Daily

Union listed the location of four different telegraph companies in the city

and the areas to which they were able to transmit messages:

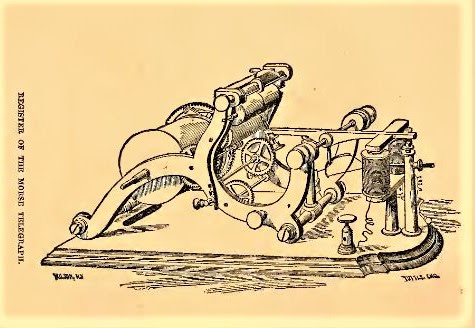

House’s Printing Telegraph, National Hotel, entrance on Sixth St, one door north of Pennsylvania

Ave. To New York via Baltimore, Philadelphia and intermediate points;

connecting at New York with Eastern Line to St. Johns and the Western Line to

New Orleans.

Magnetic Telegraph, National Hotel, corner of Sixth St. and Pennsylvania Ave. To New York

connecting as above with the extreme East and West.

Southern Telegraph, National Hotel. To New Orleans via Alexandria, Richmond, Augusta, and

Mobile, and intermediate points, including all seaboard cities.

Western Telegraph, Pennsylvania Ave between Sixth and Seventh Sts, over Gilman’s drugstore. To Wheeling and intermediate points connecting with all the Western and Northwestern points.

In 1848, for the first time, the country held its presidential election on the same day nationwide. Having the results the next day was made possible by the telegraph.

From Homans’ Cyclopedia of Commerce 1853:

Gutta Percha—a valuable substance known only within the last few years. It is the concrete juice of a large tree (Isonandra gutta), growing in certain parts of the Malayan Archipelago. The first specimen of the inspissated juice which appeared in England, was presented to the Society of Arts in 1843, but two or three years elapsed before a just sense of the importance of the substance began to gain ground. In 1845 the importation of gutta percha into England amounted to only 20,600 lbs.; in 1848, it had reached 3,000,000 lbs.; in 1851, it amounted to 30,580,480 lbs. The honor of having drawn attention to its real nature and uses is due to Drs. D’Almeida and W. Montgomerie. The purposes to which gutta percha is applied are too numerous for recapitulation. It resists the action of water and is at the same time a bad conductor of electricity; it is, therefore, employed for enclosing the metallic wires used in the electric telegraph. The efficiency of the Submarine Telegraph is largely due to this valuable substance.

...and Like the Modern Internet...

People back then became just as wound up and angry over the telegraph not functioning as we are today when the internet goes down or our computer crashes.

MOST VILLAINOUS OUTRAGE!

The New York Herald June 23, 1848 Page 3

Ever since the establishment of Morse’s telegraphic line between this city and the South, the wires have extended only to Jersey City, which rendered it frequently very inconvenient for the newspaper press, as well as others of this city. It was ascertained a short time since that the current would pass just as well under water, if the wire was covered with gutta percha, as if suspended in air; and those having charge of Morse’s line thought it would probably be well to try the experiment, and, accordingly, procured the wire, covered with gutta percha, doubled, making the covering about a quarter of an inch thick to prevent all possibility of water penetrating to the wire, and extended it across the river from Jersey City to the foot of Courtland Street. An examination discovered that it answered the desired end most admirably. It was put down on Thursday of last week, and up to 4 o’clock on Sunday afternoon, there was no obstruction. On Monday morning it was found that there was no current across the river and after having frequently tried to get a communication, they set to work yesterday and took up the wire. The secret of the stoppage of the current was then found out. On Sunday night, some malicious villain raised the wire, and after having gashed the gutta percha in several places, succeeded in breaking the wire. This is an outrage, not only upon the telegraph company but upon the whole business community of the city; and the perpetrator of so foul and contemptable a deed, deserves only to live the remainder of his days in the State prison. It would be well for the company to offer a reward of not less than five hundred dollars, for the apprehension and conviction of the scoundrel. By offering such a reward, there is a possibility of finding him; but it will be impossible to effect so a desirable end by holding out a small reward. There will be another wire, with four coatings of gutta percha put down at once and the company will liberally reward the captains of vessels, pilots, or anyone else who will be on the lookout for such villains, besides keep a watch constantly during the night, passing from one side of the river to the other. It is a matter of which the public is concerned, and all necessary means will be taken to ferret out the offender and bring him to punishment.

You can get a feeling for how long it took news to travel before and after the telegraph from the clipping below.

TELEGRAPHIC DESPATCH

The New York Herald --June 23, 1848 page 2

TELEGRAPHIC DESPATCH—We believe the quickest dispatch by telegraph, distance and all considered, was that received by us and published by us announcing the first news of peace with Mexico. The steamer Edith arrived at new Orleans on Tuesday, the 30th of May, with accounts of the ratification of the treaty by Mexico. We received the same in New York on Friday, the 2cd of June, and sent it on the same day to Boston. Thus, the news passed from New Orleans to Boston in about three days and a few hours.

By the 1st to the 15th of July, it is expected the line will be open all the way to New Orleans, by which a circuit from that city to Quebec in Canada, a distance of over 3,000 miles, will be formed and which will be equal to the distance across the Atlantic, from the United States to England. We understand that as soon as the line is through to New Orleans it is proposed to connect the lines between Quebec and New Orleans, and by that means messages can be sent the whole distance between the two points within a few minutes. If this be successful—and there is no room for doubt—it would prove, theoretically, at least, that if a line were laid across the bottom of the sea, from this city to England, communication might be obtained between the two places, within the same time it takes the fluid to pass between New York and Jersey City.

Such an undertaking would, at first sight, look chimerical; but the magnetic telegraph at the present day is as much imperfect in its infancy, as the principle of propelling vessels by steam was in the days of Robert Fulton. The principle has only just been discovered; and we have no doubt, that the mode of applying it will be as much improved upon hereafter, as the principle which Fulton discovered has been improved upon since his time.

Great as have been the inventions of the present age, they will be cast in the shade by others that will succeed them. What we have discovered, will, in the manner of practically applying them, be as much improved upon, as the manner of applying steam as an agent of propulsion, has, from time to time, been improved upon. Next to Fulton’s discovery, the magnetic telegraph deserves to rank as the first discovery of the present age.

Comments

Post a Comment