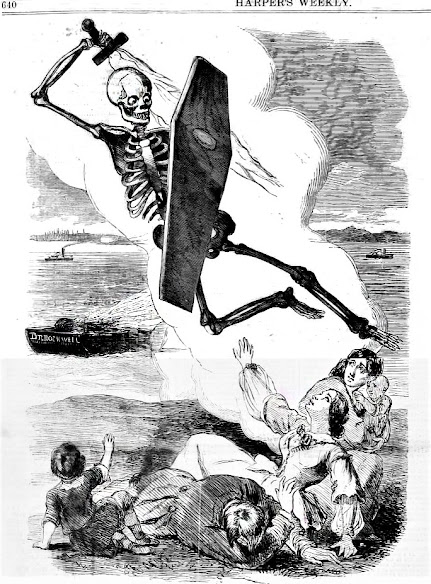

The Death Storm--1855 Norfolk, Virginia

It was summer when the dying started. The source outright lied, insisting there was no problem and left quarantine. Some authorities failed to report the disease or did not recognize the problem until it was too late.

It was contagious. It

was not contagious.

Many people hardly knew they had been infected while fifteen percent of the infected died horrible deaths, insane with fever, spewing black vomit and gasping for breath. The immigrant poor, stuffed twelve or more to a room, suffered disproportionately.

Dozens of doctors and

nurses died while tending the sick. Cemeteries and grave diggers would have

been overwhelmed if coffins had not been in short supply.

Physicians tried all

manner of treatments. Nothing worked. Masks and quarantine proved to be no defense

at all. Businesses closed so the remaining healthy population ran short of

supplies. Banks closed, so the living had no money. News outlets ceased operating,

so rumor ran rampant. Dogs and cats roamed the streets, starving because their

masters were dead. Looting the homes of those that had fled or died was

widespread. Nearly all the police were dead. An orphanage was established which

quickly filled up with several hundred children.

Then, it abated. By

the end of October 1855, “The Death Storm,” as the residents of Norfolk and

Portsmouth, Virginia called it, disappeared

Yellow fever had

struck and left. A cause and cure were nearly a half century in the future.

The ship Ben

Franklin anchored off Portsmouth Virginia the morning of June 7, 1855.

His ship needing repairs, Captain Bynum hoped to have those completed at the

Gosport Navy Yard neighboring Portsmouth. Following normal procedures, the

harbor health inspector came out to inspect the ship’s papers and determine the

health of the crew before allowing the Ben Franklin to dock. Captain

Bynum admitted the ship had come up from St. Thomas in the West Indies but that

there was no disease in the ship-despite the fact two crewmen had died on the

trip. Nonetheless, yellow fever was known to be widespread in St. Thomas, so

the Ben Franklin was sent to anchor offshore for a quarantine

period of two weeks. The harbor health inspector may have noticed a stench

rising from the cargo holds, but that was hardly considered a health threat.

Probably through a bureaucratic mistake, the Ben Franklin was

released from quarantine early June 19 and allowed to proceed into Gosport to

begin repairs on June 21.

There, a ship’s

carpenter was called aboard to re step a mast, that is to reconnect and brace

the base of a wood mast to the ship’s keel. Once aboard, the carpenter declared

the bilge water too deep and the stench so powerful it was impossible to re

step the mast until the bilge water had been pumped out, the cargo hatches

opened and the smell allowed to dissipate. No ship’s bilge water smells like

roses, but after the Ben Franklin began pumping its bilge into

the swamp area bordering the wharves, houses in the area closed their windows

and doors to keep out the smell.

In St Thomas, infected

mosquitos had laid their eggs in the ship’s bilge water. The swamps surrounding

Portsmouth and Norfolk were ideal breeding areas in summer.

On July 5, an Irish

laborer repairing the Ben Franklin fell ill. He died two days

later. A local physician, Dr. Upshur, correctly declared the man had died of

yellow fever.

For a week or so

afterwards, the public did not believe him. “Upshur’s Illness,” as some

scornfully called it, could not be yellow fever. The port had a reputation for

being a healthy area. Yellow fever was familiar to ports and doctors further

south. New Orleans had suffered a terrible epidemic two years before. There had

even been an epidemic in Norfolk 32 years before, and as many as ten epidemics

had plagued New York City since its founding. Overall, though, the disease

remained endemic to ports further south and particularly to the Caribbean.

It was believed at the

time “unhealthy miasmas” arose from water during summer in low lying areas

causing widespread disease. Charlestonians, for instance, regularly spent

summers further inland or even went to upstate New York for the summer months.

Soon, more of the dock

workers, nearly all recent Irish immigrants living in cramped tenements along

the swamp banks, fell ill. Local authorities displaced the Irish and burned

down the entire slum area. It had no effect on the disease’s progress and left

the Irish homeless.

By late July, yellow

fever had crossed the river to Norfolk. As the disease spread rapidly in early

August, the citizenry of both cities became alarmed. Many of the wealthier

started to leave for second homes on higher ground. As panic grew, store owners

closed, gathered their families, and left. Surrounding towns imposed

quarantines or outright prohibitions on the mass of refugees pressing inland or

looking for passage across the Chesapeake to Baltimore.

The disease was caused

by a virus infecting the Aedes aegypti mosquito, a native of

Africa. The mosquito’s bite transferred the virus to people where it gestated

from two to four days. It was a cunning disease. The victim became very sick,

with headaches, pains, fever and a number of other complaints, generally

recovering after about six days. For about fifteen percent of victims, the

recovery lasted only twelve to twenty-four hours, after which the disease

returned with deadly ferocity. The victim’s skin turned an orange or bronze color

after which their fever rose extremely high; delirium followed along with

spewing copious quantities of black vomit. Doctors estimated half of the

patients who reached this state died.

The frightening aspect

of the malady was its randomness. It seemed to be contagious because the

mosquitos would bite numbers of people congregated together. Otherwise, doctors

noted victims who had been sent to areas with low infection did not pass it on

to the doctors and nurses there.

As the August heat

bore down, the situation became desperate. Banks closed and transferred all

funds to their headquarters in Richmond. By now, the yellow fever epidemic was

front page news throughout Virginia and across the country. Towns and civic

organizations formed “Howard Committees” to collect funds and goods to send to

the stricken area. Named for a New York doctor decades before, a “Howard

Committee” was the term for any ad hoc group set up for some charitable

purpose. By now, though, there was difficulty getting money and goods to Norfolk

and Portsmouth. The executive of a steamboat company in Baltimore volunteered

to take doctors and nurses into Portsmouth free of charge. The Seaboard

Railroad committed to bringing medical and food supplies into the area free of

charge.

It was a religious

age, and ministers of all sects volunteered to administer last rites and

comfort the ill. Doctors and nurses volunteered from as far away as upstate New

York and as close as Richmond to come at their own expense to care for the sick

and dying.

An area for a mass

grave was established and a tent hospital set up in the horse racetrack outside

of Norfolk. Many volunteers would be buried there along with their patients.

By mid-August the

local newspapers ceased publishing—their editors and employees either dead or

fled.

Ft Monroe sat across

the water from the harbor. It was mostly a collection of crumbling buildings,

but to many minds in the epidemic area, it might well be a much healthier

place. A committee of men from Portsmouth and Norfolk went to Washington, DC to

ask President Franklin Pierce for help.

President Pierce

received them courteously and listened to them intently. He promised to have an

answer the next day. He met with his cabinet later that afternoon.

The following morning,

Pierce told the committee the cabinet members and he had put together a

personal contribution of $365 for the relief efforts but the fort could not be

used, as much as it pained him to say. He had authority to move the eleven

hundred men out of the fort and transfer them elsewhere, he explained, but he

had no authority over the soldiers’ wives and children to compel them to move

nor the budget to pay for moving them. Moreover, it would take so long to move

even the soldiers, it would be of little help to the stricken area. Clearly

disturbed by the negative answer he delivered; Pierce offered to contribute

much more money from his own purse as needed.

The only direct help

the Federal government delivered was the Secretary of the Navy authorized the

Navy base commander in Gosport to immediately give priority to building coffins

gratis for the cities and to open the Naval Hospital to civilian patients.

As bad as matters

were—they got worse.

Norfolk’s mayor died.

Portsmouth was without government as there were not enough members of the city

council to form a quorum. All the policemen were dead in Norfolk and the

remaining council there appointed one volunteer. Surrounding areas tightened

their quarantines. An ad hoc orphanage formed in Norfolk was now far too

overcrowded. A committee of couples in Richmond offered to take in one or two

each the children while the city would care for the rest.

Cures for yellow fever

were diverse and, by modern standards, appalling or whimsical. A balloonist

declared taking large cannons into the air above the cities and firing a number

of rounds was sure to drive out the illness. One doctor averred he had never

lost a patient rubbed with whiskey and red pepper over their whole body.

Another said the most important thing was to “make sure the patient is not

frightened.”

Several doctors

compared weather reports against mortality rates in New Orleans in 1853 to the

mortality rates and storms in Norfolk. They could see a clear correlation in

the rise of deaths after storms but attributed it to “lightening polluting the

healthy air.” It was noted yellow fever always disappeared after the first or

second frost when thunderstorms generally ceased.

Others argued it was

simply because colder weather suppressed “malicious miasmas” from rising.

By the end of October,

the epidemic was over. Estimates of 2,700 to more than 4,000 people had died

out of a population of 14,000 to 20,000. Nearly everybody had suffered the

disease to some extent and most families had lost one or more members.

A grateful Norfolk acknowledges the Howard Association of Richmond's Efforts and admitting as many as two thirds of the population required some of the money.

People commented that

curious insects with four narrow, pointed wings seen so often during the summer

it was nicknamed the “plague fly,” had disappeared.

The following year,

Norfolk commissioned a forty foot tall marble monument to the heroes of the

epidemic and honoring the dead.

Comments

Post a Comment