Commodore Perry Returns

Perry now turned his attention to the small

islands between Japan and China. At the time, several of these were small

kingdoms. At each, Perry exacted a treaty similar to the one he would

negotiate with Japan. The treaties provided sailors washed ashore would be well

treated; that the king would sell supplies to American ships, in return

Americans would buy from nobody else on the islands; and, that the kingdoms

would serve as coal storage points for the American navy. This last part

encountered opposition. The islanders had no wish to be responsible for

coal that might be washed/blown away in a typhoon, pilfered by the natives, seized

by pirates or other navies, etc., and then suffer the threatened consequences by

the US Navy.

A Russian fleet had reached Japan only a few weeks

after Perry in 1853. The Russians left

hurriedly without a treaty on hearing the Crimean War had started and guessed

the French and British Far East Fleets would soon come chasing them.

In early 1854, Perry received word the French and

British were preparing to send delegations to Japan to negotiate treaties. Now,

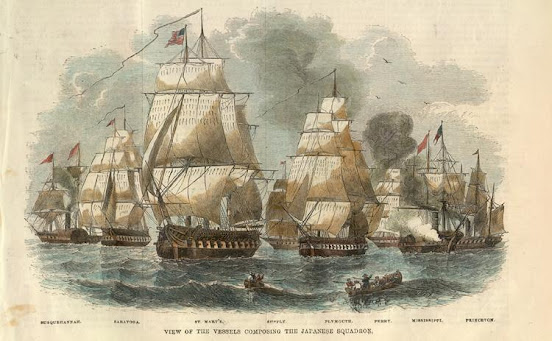

in charge of a fleet of eight ships, Perry decided he would beat them to it and

return before July 1854. He had given

the Japanese government a year because he knew the shogun would need a

long time to summon daimyos (noblemen who each governed a province) and

to adjust to coming out of isolation.

Perry stopped at Formosa, now Taiwan, and found it occupied by indigenous headhunters and descendants of Chinese farmers. He urged the US to annex the island as it would be useful in the future as a repair and coal station.

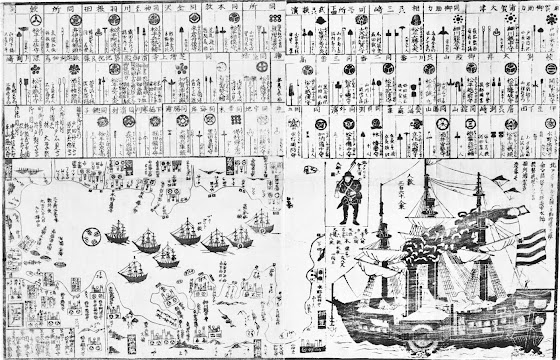

On February 11, 1854, Perry’s ships arrived in Yokohama

harbor, a move calculated, Perry later wrote, to demonstrate he did not bow to

the power of the Japanese nobility.

Foreigners were always directed to Nagasaki as Perry was when he entered

Uraga Bay near Yokohama harbor in July 1853. Yokohama was

close to Edo, the capital, and home of the shogun and emperor.

USS Susquehanna in NY Harbor

To emphasize his power, Perry would only directly deal with

the shogun’s or emperor’s highest representatives, leaving his officers

to deal with any lesser noble bearing messages. By the beginning of March, the Commodore had

grown weary and angry with Japanese delay in starting negotiations. Perry made

a flat out threat to summon a hundred ships in the next twenty days to bombard

and lay waste the city and palace. There

were not a hundred ships in the entire US Navy but the Japanese did not know

that. Negotiations started March 8, 1854. By March 31, 1854, “The Treaty of

Peace and Amity” was signed.

A color print of Perry landing

The Americans agreed to use only the

ports of Shimoda and Hakodate; and a consulate in Shimoda

Sailors would be treated well and

foreigners would be allowed to live and travel in Japan

The Japanese government was to have a

monopoly selling supplies to American ships.

A currency rate of exchange was to be

set up facilitating trade between the two countries

Mutual peace between America and

Japan

If Japan concluded a more favorable

treaty with another foreign power, the US was to receive the same extra

benefits

(now called a “most favored nation”

clause)

Given the distances, a year and a half was allowed for the

treaty to be ratified.

Perry never returned to Japan after the treaty was

signed. Congress voted him a $20,000 grant

for his services, commissioned him to write a full report of his service in the

Far East, and promoted him to rear admiral on the retired list. Perry devoted himself to what became three volumes

of Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron in the China Seas and

Japan finished at the end of 1857. Gout and years of very heavy drinking

caught up with him and he died in New York City on March 4, 1858, survived by his

wife and nine of their ten children.

While remembered today for the trip to Japan, Matthew Perry’s

career was studded with outstanding military achievements. His father had been a captain in the American

Navy in the late 1700s. His older

brothers, including Oliver Hazard Perry, a hero of the War of 1812, were all

captains. Matthew Perry began his career in 1809

and liked to say while his brother was a hero of the War of 1812, Matthew had

fired the first shot. An enthusiastic backer of modern technology and instruction,

he supervised the construction of the first steam powered American warship, USS

Mississippi, and was its first captain.

He helped modernize the curriculum for cadets at Annapolis. In the Mexican American War, he saw combat personally

leading 1,700 men in the successful assault on San Juan Bautista. In the interim

he fought pirates in the Mediterranean and served in the squadron interdicting slave

ships off the west coast of Africa.

Obit of Perry in Harper's Weekly March 1858

British set out in 1854 for Japan

Comments

Post a Comment