Before Rosa Parks There Was Elizabeth Jennings

Record breaking heat blanketed the city of around a half million. Horses,

dogs, and hogs had died in greater numbers than usual from heatstroke. As

usual, the city was slow to remove animal carcasses from public streets. Too,

two hundred tons of horse manure a day was deposited by the 22,000+ horses

pulling wagons and carriages in the city.

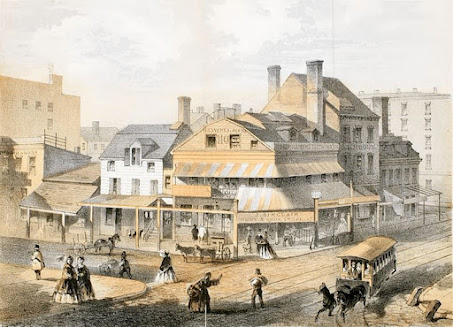

Elizabeth and Sarah were running late July 16, 1854. A two mile walk

through heat and what must have been an awful stench, was not appealing.

Wearing inch and half heel boots and "pages" --loops of rope

sewn into and around their skirts used to pull a lady's skirt up several inches

to avoid mud, horse manure and worse-they made their way down Third Avenue.

They

saw street car # 6 of the Third Avenue Railroad. For five cents each, they could at least ride out

of the sun.

At

the time, avenues in New York City were each served by an independent

"railroad" franchised by the city. Each had their own cars,

employees, policies, etc. All of them discriminated against African Americans.

Each had a car marked "Colored Only." A single car, it made a

circuit every hour or so, too long for Sarah and Elizabeth to wait.

Sixteen feet long and horse powered, the light

green streetcar moved by so slowly they had no trouble hopping onto the back

platform. Long benches faced each other the length of the

streetcar. There were still seats.

The

conductor was talking with the driver when the women got on.

Turning, he saw them and made his way to the back platform. Both women

had their nickels ready.

"Get off this car at once and wait for

the colored car," he told them.

“We’re

respectable women on the way to church and have as much right as anybody else

to ride in this car." Elizabeth answered, firmly without raising her voice.

“Wait for

the car for your people,” the conductor answered.

“We’ll

wait right here on the platform of this car,” Elizabeth answered.

Eventually,

the “colored people car” pulled up behind them. It was full. There were no

seats.

“Alright,”

the conductor grumbled and took their money. “Have a seat but if anybody

complains, I’ll throw you out.”

“I am a respectable New York native and I

have never before been insulted on my way to church,” Elizabeth snapped.

“I was born in Ireland and don’t care where you were,” the

conductor was angry.

“It makes no difference where a man is born as long as he

behaves properly,” Elizabeth retorted. “You’re a good for nothing insulting

people on their way to church!”

“That’s enough! Get

out of this car!” He moved to grab her.

“Don’t you dare lay a hand on me!”

The conductor grabbed her by the shoulders and tugged her

towards the rear platform. Elizabeth resisted by holding onto a window

frame. Unable to pry her grip loose, the

conductor called to the driver to stop and come help him.

He and

the driver wrestled Elizabeth to the back platform and shoved her off head

first, laughing as she tumbled headfirst into manure and filth.

Bleeding

from several scrapes on her face and arms, her clothes dirty and torn, her hat

crushed, Elizabeth got to her feet. The conductor laughed, and the streetcar slowly

continued on. Sarah stepped off the

platform and started towards Elizabeth. Silent

and angry, Elizabeth ignored her and took a few steps back towards home.

Suddenly,

she turned around, ran after the streetcar and jumped onto the rear platform

again.

Enraged, the conductor screamed, “You’ll suffer for this,” and

pushed her against the wall. “Driver, lash the horses and don’t stop for anyone

until we see a policeman!”

The

driver cracked his whip and the streetcar jolted forward at a pace too fast to

safely jump off.

Seeing a policeman, the driver halted, and the conductor ran over to

explain what the trouble was. Nodding, the policeman stepped on board and

instructed Elizabeth to leave at once.

"The conductor says you're causing a disturbance and upsetting the

passengers," the policeman stated. A murmur of "Not her,

him," ran through the crowd. Several people told the policeman plainly,

the woman were not causing any trouble and they had no problem with her

continuing to ride.

“Get

off this car!” the policeman ignored the other passengers.

Elizabeth

stood her ground.

But

the policeman and the conductor were too much. Again, she was pushed off the

car. “I’ll get redress for this!” Elizabeth declared.

“Yeah, see if you can,” the policeman laughed. "How you

going to do that? Colored lawyers ain’t allowed and no white lawyers going

to take a colored gal's case."

She turned

to the conductor. “What’s your name?”

“Moss,”

the conductor smiled viciously, “Edwin Moss. I’ll write it down for you.” Moss

scrawled his name on a scrap of paper along with “car #7.” He assumed a black woman could not read or

write, but Elizabeth had already noted it was car #6.

“Go on!

Git!” the policeman smacked his billy club in one hand and stamped his foot.

“Chased me

off like a dog,” Elizabeth recalled later.

Elizabeth Jennings

Jennings did find a lawyer—Erastus Culver was the most expensive and respected lawyer in the city. Then, Culver said he did not have time to try her case--he was in a tight election race for a judgeship. He passed the file on to his clerk, a junior lawyer called “Chet.”

"Chet,"

had never covered himself in glory. He'd meandered through a variety of

colleges and parties. Finally, he settled on law, though nobody thought

he'd go far. The Jennings case would be his first trial.

The young

lawyer filed her case in the Second District of the New York Supreme Court, not

in a city court.

Six months

after being tossed off the streetcar, Elizabeth got her day in court in

Brooklyn, the honorable William Rockwell presiding. The conductor and driver blandly admitted to

throwing Elizabeth off the streetcar trusting an all-white jury to acquit them.

Immediately, lawyers for the streetcar company asked the judge to dismiss

charges against the company because the conductor and driver admitted responsibility.

Judge Rockwell was as well known and respected as Chet’s mentor Culver. Rockwell agreed with the company lawyers and

announced further, that he then couldn’t charge the driver and conductor

because there was no law against their following company policy.

Chet saw

his first case about to end without even starting. Waving a book of New York statutes

Chet begged to remind the court that a New York law of 1824 declared all public

transport companies were liable for their employee’s actions.

Below, is a local

paper's account of the trial:

The Brooklyn Eagle

Feb. 13, 1855

The Case of Elizabeth Jennings versus Third Ave Railroad Company

in Brooklyn Circuit before Judge Rockwell. The plaintiff is a colored lady, a

teacher in one of the public schools and the organist in one of the churches in

this City.

She got upon one of the Company’s cars last summer, upon the

Sabbath, to ride to church. The conductor finally undertook to get her off,

alleging the car was full, and when that was shown to be false, he pretended

the other passengers were displeased at her presence; but as she saw none of

that, and insisted on her rights, he took hold of her by force to expel her.

She resisted, they got her down on the platform, jammed her bonnet, and soiled

her dress, and injured her person. Quite a crowd gathered around but she

effectually resisted, and they were not able to get her off. Finally, after the

car had gone further, they got the aid of a policeman and succeeded in getting

her from the car. She instructed her attorneys, Messrs. Culver, Parker and

Arthur, to prosecute the Company, together with the driver and conductor. The

latter two interposed no defense, the Company took issue and the cause was

yesterday brought to trial. Judge Rockwell gave a very clear and able

charge, instructing the Jury that the Company were liable for their agents, whether

committed carelessly, negligently, or willfully and maliciously. That they were

common carriers and as such were bound to carry all respectable persons; that

colored persons, if sober, well adorned, and free from disease had the

same rights as others and could neither be excluded by any rules of the

Company, nor by force or violence: and in case of such expulsion or

exclusion, the Company was liable.

The plaintiff claimed $500 in

her complaint, and a majority of the Jury was for giving her the full amount:

but others maintained some peculiar notions as to colored people’s rights, and

they finally agreed on $225, (about $7,000 in 2021) on which the Court added ten percent besides the costs.

Railroads, steamboats,

omnibuses, and ferry

boats will be admonished from this as to the rights of respectable colored

people. It is high time the rights of this class of citizens were ascertained,

and that if it should be known whether they are to be thrust from public

conveyances while German or Irish women, with a quarter of mutton or a load of

codfish can be admitted.

Elizabeth Jennings went on to become a respected educator founding the first kindergarten for African American children. She died in New York City in 1901, aged 74.

Chester A. Arthur became 21st president of the United States. He is known to historians today as the president who instituted the Federal Civil Service as a means of combating corruption in government.

Sadly, over a hundred years later, by the time Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus, Elizabeth Jennings had slipped into obscurity.

Comments

Post a Comment