Women's Clothes Pt 2--Green Poison and the Cephalometron

In the gas light her green dress and blouse shimmered.

This sort of green would make any woman alluring--and deadly. She had about her

enough poison to kill a dozen or more suitors. There were thousands like

her--every one of them poisonous. And every one of them dying.

And it was dye that led to their dying.

In

the early 1820s, a German chemist invented a recipe to dye cloth a vivid,

brilliant green. It shimmered, particularly in gas light which was

becoming more popular in homes. In contrast to all the duller and

less stable dyes of the era, "Emerald green" as we know it

today, kept its color . "Deadly green" would have been a

more accurate name. The secret to the dye was a combination of copper and

arsenic trioxide. As one chemist put it later, a woman's emerald green

ballgown contained enough poison to kill dozens of suitors. Even today,

clothing conservators wear masks and gloves to work on emerald green clothes

from the period.

The more

frequently a woman wore this green the more frequently sores opened up on her

body, raw sores that absorbed the poison even quicker. The wealthy were

probably less affected because they wore a constantly changing series of

dresses. It was the middle class that suffered. A middle class woman

might well possess only one or two dresses for formal wear. And if one of

them were emerald green...

Shoes were an obsession for some women

Shoes from the period one sees in a museum, often look almost

like ballet slippers. Walk in those? No. They didn’t. Those were

slippers to wear in the house or if riding in a carriage.

Ankle boots with sturdy one inch high heels were for walking

outside. With thick one and half inch heels and leather uppers,

shoes either laced or buttoned. Unpaved streets were muddy, covered with

horse droppings or worse. Walking outside, ladies wore leather high heels.

House shoes, what we would think of as slippers, were worn at home.

There was not yet a concept of right or left shoe, so for some

designs it did not matter which shoe went on which foot. For other designs,

particularly if they buttoned up on one side or the other, a shoe was obviously

a right or left shoe, but not because of the way the sole and upper were

designed.

Most respectable houses of the time had a boot scraper, simply a

cast iron strip two inches high set upright by the door. Men and women could

scrape the bottom of their boots, before being admitted to the house.

Green silk house shoes 1850s--

probably loaded

with poison

Fits, Fits, Fits. I cannot imagine any shoe maker using

advertising wording today like the kind in the ad below.

Don't Go Using Those India Rubbers!

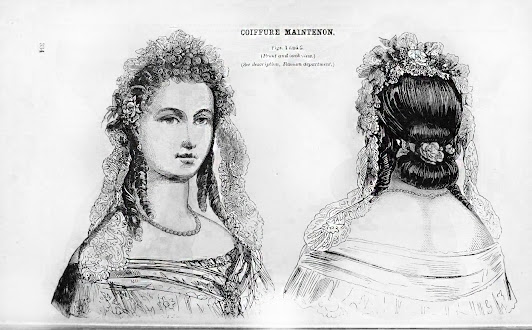

Hairstyles & Hats

Elaborate styles were considered suitable for unmarried young

women only. Once married, a woman's hair style was likely to become more

simple, even severe her hair gathered up in a bun and worn on the back of the

neck.

The most popular formula for hair care was combination of water,

oil, and eggs. Washing one's hair more than several times a month was

considered possibly counter productive. In between washings women were to

brush their hair nightly a certain number of strokes.

Married woman early 1850s

Godey's Book 1863

Young woman mid 1850s

Young Woman 1859

Woman

1865

Upper class women would never go out in public without a hat.

Even at home they and women of all classes wore a sort of veil handkerchief on

their hair. Women doing heavy farm work wore a scarf, a sun bonnet or a broad

brimmed straw hat. Pale skin was as desirable beauty trait as it showed a woman

did not work outside. Sun tans were not wanted.

Godey's Book Bonnets of the 1850s

At a "Watering Place"

Godey's Book 1863

THE GREAT

CEPHALOMETRON!!

Make up was considered the sort of thing only a “fallen

woman,” or one with no sense of propriety would wear. This did not prevent all

sorts of beauty routines being adopted for skin care, hair coloring, and lip

paint, all using what would be called now, “natural organic materials,” which,

oddly, did not seem to be considered "make up."

Comments

Post a Comment